Learning Jest Through Practice

Jest is a Javascript testing framework published by Facebook. When browsing the official website homepage, three points are highlighted in particular: no configuration, improved performance, and easy mocking. Are they marketing promises, or reality? To answer this question, we will test Jest on a basic React project and explore its various possibilities.

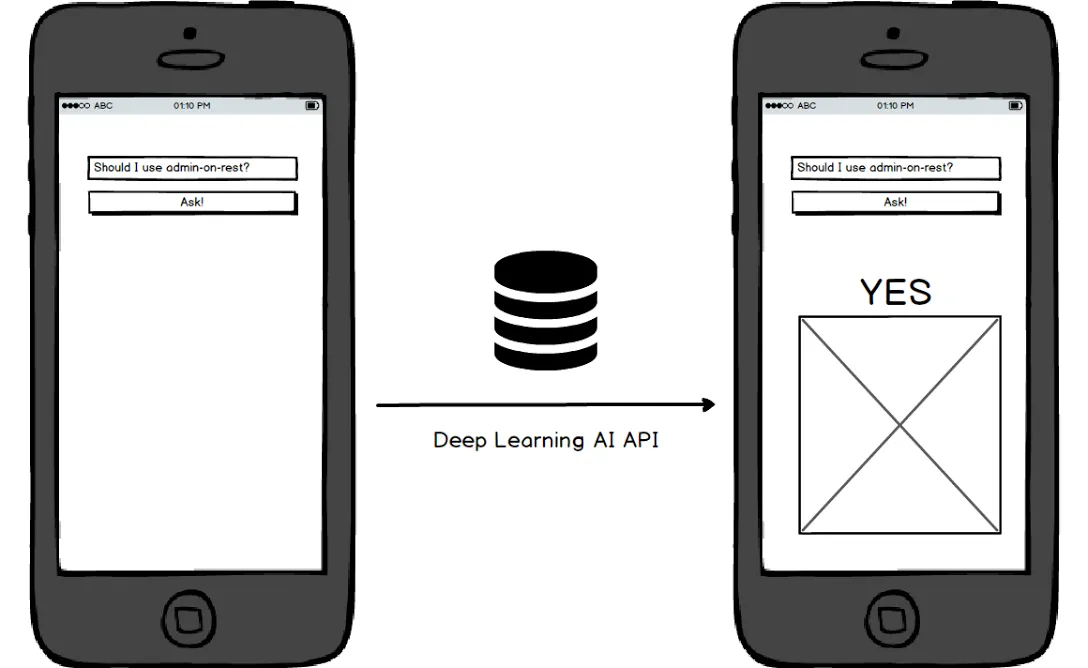

Yes-No Application

Let’s consider a very simple application where the user enters a question, and an AI answers by yes or no. The mock-up looks like the following:

This application consists of a text input and a button. When the user clicks on the button, we display an answer (“yes” or “no”) with an illustration image. Quite simple, but perimeter would be enough to test main Jest features.

The answer comes from a sophisticated deep learning random API: https://yesno.wtf/api/. It returns either a yes or no answer as a JSON response:

{ answer: "no", forced: false, image: "https://yesno.wtf/assets/no/14-cb78bf7104f848794808d61b9cd83eba.gif"}As a side-note, it doesn’t always return yes or no, as explained on the website:

To make things more exciting, we return

{"answer": "maybe"}every 10.000 times.

We can also pass a force parameter to set an expected response. Yet, let’s postpone the implementation of this parameter in a future version of our YesNo application.

Using Create React App

We are going to use create-react-app in this post. create-react-app is a tool bootstrapping a pre-configured ready-to-use React project. For instance, it handles Hot Module Reload (HMR) allowing us to selectively reload a component we just changed, instead of reloading the whole page.

# install create-react-app globallyyarn add -g create-react-app

# bootstrap React application in `yesno` foldercreate-react-app yesnoThis command creates several files and folders. The most interesting files are in the src folder:

src/ ├── App.css ├── App.js ├── App.test.js ├── index.css ├── index.js ├── logo.svg └── registerServiceWorker.jsThe main file of our application is the App.js file. It contains a single render method displaying our page. It is the file we are going to change in this tutorial.

To launch our application, we just need to execute:

yarn startIt should then open a browser tab on http://localhost:3000 with our current application:

www.jonathan-petitcolas.com might track you and we would rather have your consent before loading this.

Note: if you are using a version control tool (like git), do not forget to initialize it at this step. Even if the yes/no tool does a big amount of things by itself, it doesn’t know wheter the project should be versioned.

Installing Jest

Jest is already installed with create-react-app. However, if we use a React project created from scratch, we need to install it manually using the following command:

# only for React app created from scratchyarn add -D jest babel-jestWe installed an extra package in the previous command: babel-jest. Thanks to this package, Jest will use our .babelrc file to better understand JSX and ES6. We install these two dependencies as development (-D) dependencies, as they are used only for testing purposes.

By default, Jest looks for all files suffixed by .spec.js or .test.js. In the current project, we have a .test.js suffixed file. So, no need for extra configuration. Note that Jest also takes into account all files found in __tests__ folders.

To execute our tests, we can use:

./node_modules/.bin/jestHowever, with a create-react-app application, we don’t have any .babelrc file at the root level. Hence, we need to use the react-script wrapper to launch Jest correctly. Fortunately, create-react-app already uses this wrapper through the following command:

yarn testWhich produces the following output:

react-scripts test --env=jsdom

PASS src/App.test.js ✓ renders without crashing (24ms)Test Suites: 1 passed, 1 totalTests: 1 passed, 1 totalSnapshots: 0 totalTime: 1.285sWe may achieve the same result using Jest binary directly in a React app created from scratch.

So Jest is correctly installed and configured. Despite a very long paragraph, there is no configuration to write in order to make Jest working. One of its promises is resolved kept!

Let’s Test-Driven Develop our App!

What is TDD?

We are now going to work on our application using Test-Driven Development (TDD). This process ensures we do not forget to test any feature, and that we are testing them right. It’s a four steps process:

- Write a test to demonstrate how an incoming feature should work,

- Launch it and see it fail,

- Write the feature,

- Launch the test and see it pass.

Then, we rinse and repeat until our whole feature is finally done. Step 2 is really important. It is not rare indeed to write a test which always passes (for example, writing an asynchronous test, and exiting before it ends). Don’t worry, we’ll see an example later in this post.

Writing Good Assertions

Based on our above mock-up, we basically need four things on our page: an input with a submit button for the question part, and a text with a picture for the answer one. Let’s write the assertions proving that the mock-up is correctly implemented. Here is our updated App.test.js file:

it("should display a text input to fill question");it("should display a submit button to send question to the Internet Gods");it("should display Internet Gods answer in both text and picture format");At this point, we just translated our product owner wishes (materialized as a backlog story) into automated test assertions.

A special care has to be taken in this part. Writing such assertions has several advantages. The most important one is the share of currently implemented business rules. When an agile project grows, it is not rare to have to implement some business rules contradicting previous ones. Having a clear understanding of why a test fails after implementing a new feature is fundamental to make a good decision about this conflict.

That’s why I strongly encourage to write some functional assertions (should display Internet Gods answer in text format) instead of technical ones (should display API answer in a title tag). This way, we may share the test output directly with our product owner (even the non-technical ones), and they can understand it without further explanations.

Writing our First Tests

So, let’s start by writing our first tests:

import React from "react";import { shallow } from "enzyme";

import App from "./App";

it("should display a text input to fill question", () => { const wrapper = shallow(<App />); expect(wrapper.find('input[type="text"]').length).toBe(1);});

it("should display a submit button to send question to the Internet Gods", () => { const wrapper = shallow(<App />); expect(wrapper.find('button[type="submit"]').length).toBe(1);});We included the enzyme library. This package is a set of utilities making React component testing easy as a breeze. The shallow method compiles our React component, but not its children. Hence, if our <App /> component contained a <CustomForm /> component, the <CustomForm /> component would not be compiled and would appear pristine in our output. This way, shallow ensures we are testing only one component at a time.

The rest of the test is self-explainatory. Note that we don’t have to include the expect() import: it is already done in jest, just like for the it() function.

Installing Enzyme on a React 16 project

As we required enzyme, we need to grab it as a dependency:

yarn add -D enzymeHowever, when launching our test suite, we encounter the following error:

Enzyme Internal Error: Enzyme expects an adapter to be configured, but found none. To configure an adapter, you should call

Enzyme.configure({ adapter: new Adapter() })before using any of Enzyme’s top-level APIs, whereAdapteris the adapter corresponding to the library currently being tested. For example:

In order to make it work, we need another extra package:

yarn add -D enzyme-adapter-react-16Then, we need to tell Enzyme to use this freshly installed adapter. So, let’s create a src/setupTests.js file:

import { configure } from "enzyme";import Adapter from "enzyme-adapter-react-16";

configure({ adapter: new Adapter() });As we used create-react-app to bootstrap our application, Jest automatically uses this src/setupTests.js file. So, we don’t have anything more to do.

If we didn’t use create-react-app, we’d have to tell Jest where to find its setup files. It is done by editing the package.json file, as follows:

{ "jest": { "setupFiles": [ "./src/setupTests.js" ] }}Now, running our Jest test suite should show us that our two tests are failing (output truncated to remove less important parts).

FAIL src/App.test.js * should display a text input to fill question

Expected value to be (using ===): 1 Received: 0

* should display a submit button to send question to the Internet Gods

Expected value to be (using ===): 1 Received: 0

✕ should display a text input to fill question (5ms) ✕ should display a submit button to send question to the Internet Gods (3ms) ○ skipped 1 testSo, let’s make them pass!

Prototyping our Application

Here is the code to make our tests pass:

import React, { Component } from "react";

import "./App.css";

class App extends Component { render() { return ( <div className="App"> <div className="question"> <input type="text" /> <button type="submit">Ask to the Gods of the Internet!</button> </div> </div> ); }}

export default App;Our test suite now looks promising:

PASS src/App.test.js ✓ should display a text input to fill question (18ms) ✓ should display a submit button to send question to the Internet Gods (6ms) ○ skipped 1 testFine! Yet, we still need to handle response display. So, let’s complete our tests like the following:

it("should display Internet Gods answer in both text and picture format", () => { const wrapper = shallow(<App />); wrapper.setState({ answer: { answer: "no", forced: false, image: "https://yesno.wtf/assets/no/0-b6d3e555af2c09094def76cf2fbddf46.gif", }, });

const answer = wrapper.find(".answer"); expect(answer.find("h1").text()).toBe("no"); expect(answer.find("img").prop("src")).toBe( "https://yesno.wtf/assets/no/0-b6d3e555af2c09094def76cf2fbddf46.gif", );});Let’s make it pass implementing answer display within our <App /> component:

class App extends Component { constructor(props) { super(props); this.state = { answer: null, }; }

render() { return ( <div className="App"> <div className="question"> <input type="text" /> <button type="submit">Ask to the Gods of the Internet!</button> </div>

<div className="answer"> <h1>{this.state.answer.answer}</h1> <Image src={this.state.answer.image} /> </div> </div> ); }}Even without launching our web browser, we can notice something is wrong in tests:

* should display Internet Gods answer in both text and picture format

TypeError: Cannot read property 'answer' of nullAnd indeed: by default, our state is not populated. Hence, JavaScript complains about displaying the answer field of a null state. Our test suite misses a special case: when there is no answer. When we notice such an edge case, we should add a test to ensure it is correctly handled. So, let’s update our test file:

it("should not display any answer by default", () => { const wrapper = shallow(<App />); expect(wrapper.find(".answer").length).toBe(0);});To make it pass and fix all other tests errors, let’s wrap our answer div into the suitable condition:

{ this.state.answer && ( <div className="answer"> <h1>{this.state.answer.answer}</h1> <img src={this.state.answer.image} /> </div> );}Then, we can proudly watch our console and read:

PASS src/App.test.js ✓ should display a text input to fill question (6ms) ✓ should display a submit button to send question to the Internet Gods (3ms) ✓ should not display any answer by default (1ms) ✓ should display Internet Gods answer in both text and picture format (5ms)

Test Suites: 1 passed, 1 totalTests: 4 passed, 4 totalSnapshots: 0 totalTime: 0.515s, estimated 1sRan all test suites related to changed files.So, our component is correctly mocked now. We can take a look at our browser, setting a hard-written answer directly in the constructor. Adding some CSS may give you the following output:

www.jonathan-petitcolas.com might track you and we would rather have your consent before loading this.

Mocking with Jest

It is time now to make some real calls to YesNo API. As usual, let’s start by writing some assertions:

describe("API Caller", () => { it("should call YesNo API"); it("should return YesNo response in JSON format");});Using Spies and Stubs

Yet, contrary to what we defined as the best way to proceed before, we are going to implement the feature before tests:

export default () => fetch(`https://yesno.wtf/api/`).then((response) => response.json());fetch is the modern successor of XmlHttpRequest or $.ajax. It allows making some network calls using promises. It is not well supported yet, and we would need a polyfill if we use it on oldest browsers or Node versions. However, we don’t really care about IE6 support in this proof of concept, do we?

As the code is self-explanatory, let’s focus on tests. We need to check which URL has been called by fetch. We can use some spies for that. A spy is an object tracking all function calls: how many times was it called? With which arguments? Jest provide an easy way to set up spies using jest.fn() function.

import ask from "./Api";

describe("API Caller", () => { it("should call YesNo API", () => { const fetchSpy = jest.spyOn(global, "fetch");

return ask().then(() => { expect(fetchSpy).toHaveBeenCalledWith("https://yesno.wtf/api/"); }); });});Let’s focus on these three lines. We start by defining a spy on the fetch method. Jest can only mock functions and object methods. We circumvent the issue using the global object. Then we call our API, and check that our spy has been correctly called, using YesNo API URL.

Note that we returned a promise in our test suite. This is done to ensure our test would wait until the end of the returned promise. Without this return, the test would launch our API call in a parallel thread, yet the test would reach its end and simply finish. All tests in our then would not be executed, causing an always green test. Not really useful, is it?

If we launch the test with the code above, we face a critical error:

TypeError: Network request failed at XMLHttpRequest.xhr.onerror (/home/jpetitcolas/dev/yesno/node_modules/whatwg-fetch/fetch.js:436:16)Our test suite broke because we made a network request. This is a really bad practice. Calling external systems within our tests increases the time to execute (network is slow), and reduces their viability. What about if the third-party system is temporarily down? Our tests should be resilient to other system failures. At least, for the unit tests. So, we need to prevent this network request. Fortunately, Jest provides a mockImplementation method:

it("should call YesNo API", () => { const fetchSpy = jest.spyOn(global, "fetch").mockImplementation(() => ({}));

return ask().then(() => { expect(fetchSpy).toHaveBeenCalledWith("https://yesno.wtf/api/"); });});We replaced the default behavior of fetch (making a network call) to a simple function, returning an empty object. Launching our tests again would give us the following output:

* API Caller › should call YesNo API

TypeError: fetch(...).then is not a functionIndeed, our code expects a promise as a return value of fetch. Not an issue: just return a Promise resolving a fake response object:

it("should call YesNo API", () => { const fetchSpy = jest.spyOn(global, "fetch").mockImplementation(() => Promise.resolve({ json: () => {}, }), );

return ask().then(() => { expect(fetchSpy).toHaveBeenCalledWith("https://yesno.wtf/api/"); });});Our test should pass. Let’s verify that is it really testing our code by making it fail, for instance by changing the URL in Api.js. Remember: a test which has never failed is not a reliable test.

It’s time now to implement our second test:

it("should return YesNo response in JSON format", () => { const fetchSpy = jest.spyOn(global, "fetch").mockImplementation(() => Promise.resolve({ json: () => ({ foo: "bar" }), }), );

return ask().then((response) => { expect(response).toEqual({ foo: "bar" }); });});It looks good. We updated the returned structure of our json method, and tested that we correctly receive this structure at the end of our API call.

Yet, if we debug our test adding the following line:

it("should return YesNo response in JSON format", () => { const fetchSpy = jest.spyOn(global, "fetch").mockImplementation(() => Promise.resolve({ json: () => ({ foo: "bar" }), }), );

console.log(fetchSpy.mock.calls); // <----

return ask().then((response) => { expect(response).toEqual({ foo: "bar" }); });});We notice something weird. Before the ask call, we already have a call to our API:

console.log src/Api.test.js:21 [ [ 'https://yesno.wtf/api/' ] ]Indeed, we didn’t reset our fetch mock between all tests. To do so, just add an afterEach function (which will be called at the end of each of our tests):

describe("API Caller", () => { afterEach(() => { jest.resetAllMocks(); });});Our console.log should not display any calls anymore.

If we didn’t use create-react-app, we may have configured this behavior globally, telling Jest to reset mocks automatically between each test. We can achieve that by editing our package.json file, and adding the following configuration:

{ "jest": { "resetMocks": true }}Yet, it is currently not supported by create-react-app (see this issue). So, we have to think about the resetAllMocks method in all our tests for now.

Mocking a Module

The only missing step for our application is to plug our <App /> component to our Api function. So, let’s update our test to represent a more realistic user behavior:

it("should display Internet Gods answer in both text and picture format", () => { const wrapper = shallow(<App />); wrapper.find("button").simulate("click");

wrapper.update();

const answer = wrapper.find(".answer"); expect(answer.find("h1").text()).toBe("no"); expect(answer.find("img").prop("src")).toBe( "https://yesno.wtf/assets/no/0-b6d3e555af2c09094def76cf2fbddf46.gif", );});Note the call to wrapper.update(). This is required as we updated the state.

We replaced the setState call by a click on the submit button. We now need to update our <App /> component to send a real API call:

import askApi from "./Api";

class App extends Component { constructor(props) { super(props); this.state = { answer: null }; }

ask = () => askApi().then((answer) => this.setState({ answer }));

render() { return ( <div className="App"> <div className="question"> <input type="text" /> <button type="submit" onClick={this.ask}> Ask to the Gods of the Internet! </button> </div>

{this.state.answer && ( <div className="answer"> <h1>{this.state.answer.answer}</h1> <img src={this.state.answer.image} alt={this.state.answer.answer} /> </div> )} </div> ); }}We added an onClick prop to our button. It calls a method declared differently of our render method. It is declared as a class variable (ask = () => {}). It allows to prevent some this binding issues, and is possible thanks to the Babel Transform Class Properties plug-in, already configured by create-react-app.

Launching our test would raise an already familiar error:

TypeError: Network request failed at XMLHttpRequest.xhr.onerror (/home/jpetitcolas/dev/yesno/node_modules/whatwg-fetch/fetch.js:436:16)Indeed: our application still calls the real API ,as we didn’t mock the Api module in the App tests. In this case, we are going to use jest.mock function. This powerful function allows mocking a module directly in the Node requirements resolution process.

jest.mock('./Api');This line changes the ./Api file resolution to __mocks__/Api.js file. Hence, if we create such a file adding the following code:

export default () => Promise.resolve({ answer: "no", forced: false, image: "https://yesno.wtf/assets/no/0-b6d3e555af2c09094def76cf2fbddf46.gif", });All calls to our Api.js file would resolve a promise with an example of successful response. With this single reusable line of code, our <App /> component is mocked.

Note that we can put this line wherever we want in the file. It uses code hoisting. Behind this obscure expression is a very simple concept: all code “hoisted” would appear at the very beginning of the file. It prevents some require resolution conflicts.

Launching our tests again gives us another error:

* should display Internet Gods answer in both text and picture format

Method “text” is only meant to be run on a single node. 0 found instead.It doesn’t find the .answer h1 title. Indeed: our API call is done via a Promise, and is asynchronous. We need to wait for the Promise to be resolved. Even if we return an already resolved promise, JavaScript waits for the next JS event loop tick before effectively resolving promises. Hence, we need to wait before testing our .answer. We can either use a setTimeout call, or better, another Promise.resolve call in our test:

it("should display Internet Gods answer in both text and picture format", () => { const wrapper = shallow(<App />); wrapper.find("button").simulate("click");

return Promise.resolve().then(() => { wrapper.update();

const answer = wrapper.find(".answer"); expect(answer.find("h1").text()).toBe("no"); expect(answer.find("img").prop("src")).toBe( "https://yesno.wtf/assets/no/0-b6d3e555af2c09094def76cf2fbddf46.gif", ); });});Finally, if we give a last look at our test suite, everything should be green. Our app is ready to be shipped!

PASS src/App.test.js ✓ should display a text input to fill question (5ms) ✓ should display a submit button to send question to the Internet Gods (4ms) ✓ should not display any answer by default (2ms) ✓ should display Internet Gods answer in both text and picture format (7ms)

Test Suites: 1 passed, 1 totalTests: 4 passed, 4 totalSnapshots: 0 totalTime: 0.232s, estimated 1sAnd here is the final interactive version. Press the button to update the answer:

www.jonathan-petitcolas.com might track you and we would rather have your consent before loading this.

We may improve rendering by setting a loader, or by hiding already displayed picture when re-submitting the form. Yet, it goes beyond the scope of this post. So, we’ll settle for this not perfect but working app.

Some Jest Extra Tips

Snapshot Testing

Another interesting feature of Jest is the Snapshot Testing. When we test a huge or unknown input, instead of console-logging the output and inserting it into a .toEqual() method, we can use the .toMatchSnapshot() function. For instance, if we want to test the total output of our <App /> render function, we can use something like:

it("should render <App /> correctly", () => { const wrapper = shallow(<App />); expect(wrapper).toMatchSnapshot();});The first time this test is executed, it records the value of wrapper, and stores it in a file saved in the __snapshots__ folder. Then, if we run the test again, Jest then compares the new test value with the stored one. If they are different, an error occurs, asking us if we want to update the snapshot file.

This feature is interesting, but should not be used compulsively. If our use case is simple, and we know exactly what we expect, it is far better to use toEqual. Indeed, reading the diff between expected and current output is easier.

I see two use cases where snapshot testing is useful:

- When joining an existing project with no tests: it allows to setup quickly a basic test coverage, which will be refined over time,

- When writing some integration tests: we just want to ensure everything works, but don’t care about implementation details.

Hence, we must be careful with this tool: with great power comes great responsability!

Interactive Filters on Jest Interface

Another Jest killer feature is its interface. In addition to its great colors and output, we can filter interactively tests we want to run:

› Press o to only run tests related to changed files. › Press p to filter by a filename regex pattern. › Press t to filter by a test name regex pattern. › Press q to quit watch mode. › Press Enter to trigger a test run.Filtering tests without setting up some .only is great! Of course, with some code reviews, with some Git hooks and with some rigor, we never skip by mistake any tests before a production deployment. Or, do we?

Conclusion

In conclusion, we are far from our past experience with Jest. No configuration, a very simple mock system, an interface designed for developers (for once, it’s a compliment!), good performances… I strongly encourage you to test it! And, last but not least: Jest is not restricted to the React ecosystem. For example, we use it on EventDrops, a data visualization project based on D3.js.

All source code of this application is available on GitHub. Take a look on commits history, each one is a step of this tutorial.

Authors

Full-stack web developer at marmelab - Node.js, React, Angular, Symfony, Go, Arduino, Docker. Can fit a huge number of puns into a single sentence.