Do you need a Backend For Frontend?

A software architecture that doesn’t align with the needs of its users leads to frustration, slow development, and poor user experiences. This is especially true in modern applications where multiple frontends (web, iOS, Android, TV) consume the same backend services. In these cases, a Backend-for-frontend (BFF) can be a game-changer.

Signs That There Is A Problem

Did you notice any of these issues in your organization?

Performance Issues

- Mobile apps making 10+ API calls for a single screen (network latency compounds)

- Over-fetching: Getting 50 fields when you need 5

- Under-fetching: The N+1 problem manifesting in your frontend

- Bandwidth constraints on mobile networks being ignored

Development Velocity Problems

- Frontend teams waiting weeks for backend API changes

- Each client (web, iOS, Android) implementing the same data aggregation logic

- Bug fixes need to be deployed across multiple codebases

- New features require coordination meetings between 3+ teams

Organizational Friction

- Backend team receives contradictory requirements from different frontend teams

- API versioning nightmares (v1, v2, v2.1, v2-mobile, v2-mobile-lite…)

- Frontend developers learning backend domain models instead of focusing on UX

- “This would be a 5-minute change if I could just modify the API” becomes a daily complaint

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. Many organizations face these challenges as they scale their applications and teams. That doesn’t mean you’re doomed to a slow, frustrating development process.

Root Causes

The fundamental issue is a disconnect between how backend and frontend teams operate. Backend APIs are typically data-centric, shaped by database schemas, while frontends require task-centric data to build user experiences.

This is a classic example of Conway’s Law in action: backend teams prioritize data integrity, and frontend teams prioritize UX, leaving a gap where no one owns the overall “API experience.” As a result, frontend developers spend too much time orchestrating and translating data from APIs not designed for their needs.

This problem is amplified by technical debt. Legacy APIs become too risky to modify, forcing frontend teams to duplicate data aggregation logic across clients, which leads to inconsistencies. Critical concerns like authentication and authorization also become scattered, increasing complexity and creating security vulnerabilities.

The Backend-for-Frontend (BFF) pattern offers a solution to these challenges.

The BFF Pattern Explained

But what is a Backend-for-Frontend (BFF) exactly?

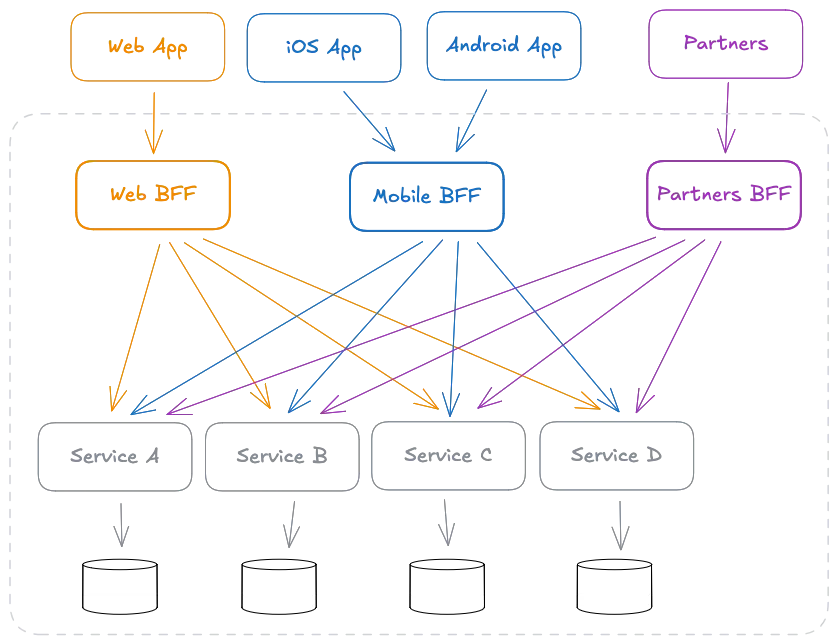

A BFF’s primary role is to streamline the client’s interaction with complex backend systems. It aggregates multiple service calls into a single request, transforms data into a frontend-friendly format, and handles client-specific logic like caching, session management, authentication tokens, rate limiting, and retry policies.

The core concept is to create a dedicated backend for each frontend application (e.g., one for web, one for mobile). This BFF acts as a translation layer, not a business logic layer, and is owned and maintained by the frontend team that consumes it. This ensures the API is tailored to the specific needs of the client application. When some frontends share similar needs, they can share a BFF, but the key is that each BFF is purpose-built for its client.

A well-designed BFF has several key characteristics. It’s a thin layer, meaning it primarily handles orchestration and data transformation rather than complex business logic. It’s frontend-driven, so its API design starts from the UI/UX needs, not backend constraints. This makes it purpose-built and highly optimized for its specific client. Finally, a BFF is disposable; it can be replaced or rebuilt when the frontend undergoes a major redesign, without affecting other services.

It’s just as crucial to define what a BFF is not. It should never contain business logic, which must remain in the backend services. A BFF also shouldn’t access databases directly, handle complex computations, or share data across different clients. Its purpose is to be a lean translation layer, not a monolithic backend.

Implementation Strategies

How you implement a BFF depends on your team’s skills, existing infrastructure, and specific needs.

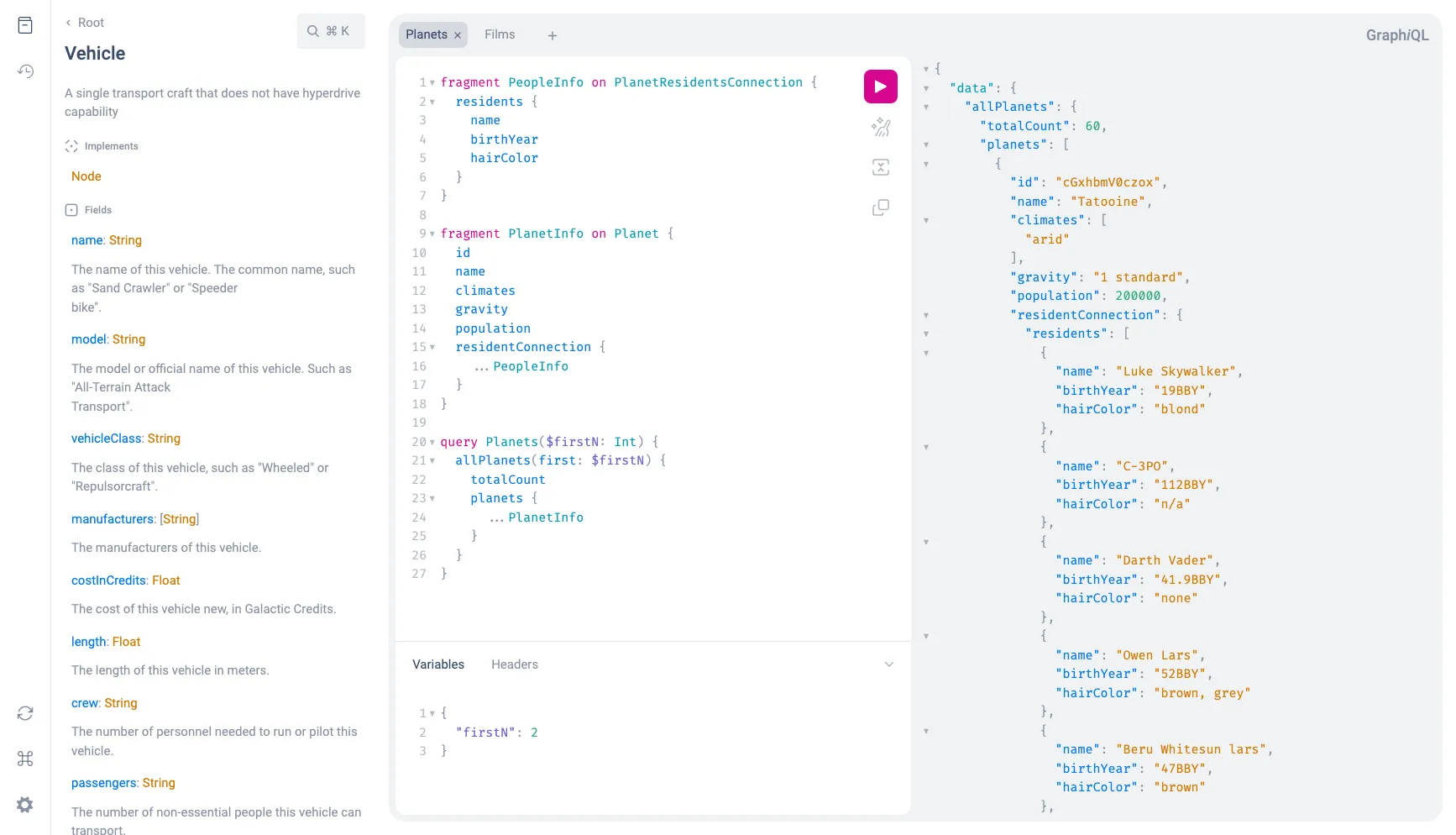

The most common approach is to build a GraphQL API, which allows frontend teams to specify exactly what data they need in a single request. This is particularly useful for complex UIs that require data from multiple backend services. It makes the BFF a single endpoint with type safety that can evolve independently of the backend services. The frontend logic is then built as resolvers for queries and mutations. However, GraphQL comes with its own challenges, including a learning curve for teams unfamiliar with it and complexities around caching, authorization, and performance.

We’ve published a series of articles on the subject, called Dive Into GraphQL, which you might find useful.

Another approach is to create a RESTful BFF. This can be simpler to implement if your team is already familiar with REST and you have existing REST infrastructure. However, it may still require multiple endpoints per screen, which can lead to similar issues as before, albeit at a smaller scale.

Some teams opt for gRPC or Protocol Buffers when performance is critical, and they need strong typing. This is more common in microservices architectures where low latency and high throughput are required. However, gRPC is less web-friendly and requires more tooling.

You can deploy your BFF in various ways depending on your architecture and team structure:

- Embedded: The BFF code lives in the frontend repository (e.g., Next.js API routes)

- API Gateway: For simple aggregation needs, you can use an API Gateway that supports request transformation and aggregation, such as AWS API Gateway or Kong.

- Standalone: The BFF is a separate service deployed alongside the frontend

- Serverless/Edge Computing: Use Lambda/Cloud Functions for on-demand scaling, deploy them close to users to improve performance (Cloudflare Workers, Vercel Edge)

Real-World Examples

The very first public mention of the BFF pattern was by Phil Calcado, a SoundCloud engineer, who described how they moved from a monolithic API to multiple BFFs to better serve their web and mobile clients, in 2015. The SoundCloud example spawned multiple articles, including ones by Sam Newman, Thoughtworks and Microsoft.

Another notable example is Netflix, which pioneered using GraphQL BFFs to serve their diverse client ecosystem. They shared their experiences in various tech articles.

Walmart is also vocal about their use of BFFs, although they recently moved away from it to a federated GraphQL approach.

We have more direct feedback, as we’ve implemented BFFs for several of our clients, two of which are public:

- Arte: The European culture channel uses a BFF to serve their web and mobile apps, improving performance and development speed. We shared the details in a case study.

- Accor: The hotel group uses a BFF to manage their booking system across web and mobile, allowing for rapid feature development. We discussed this in a blog post.

Outcomes When Done Right

When implemented correctly, the BFF pattern delivers both immediate and long-term benefits.

The most significant immediate win is a dramatic boost in development velocity. Frontend teams can ship features way faster, cutting time-to-market. Because the BFF handles data aggregation on the server-side, this significantly improves mobile app performance by reducing network round trips and payload sizes. By centralizing client-specific logic, BFFs also eliminate inconsistencies between different frontends, which reduces bugs and lowers development costs.

How this translates into real-world metrics varies by organization. Some teams report a 2-3x increase in feature delivery speed and a 30-60% reduction in app load times. To get an idea of a actual benefits for your team, you’ll probably need to run a small pilot project and measure the impact.

Over the long term, the BFF pattern fosters better alignment between frontend and backend teams. It establishes clear ownership, allowing teams to work more independently and reducing the need for coordination meetings. This autonomy makes it easier to add new client types (like TV, watch, or car interfaces) without disrupting existing services. Furthermore, technical debt is isolated to specific BFFs, simplifying maintenance and making it easier to migrate to new backend services in the future.

Is BFF Always The Right Choice?

However, the BFF pattern is not a silver bullet and comes with its own set of challenges.

Introducing more services inevitably increases operational complexity, requiring more effort in maintenance and monitoring. There’s also a risk of code duplication if similar logic is needed across multiple BFFs. Versioning can become tricky, especially with mobile clients that can’t be force-updated, and each new BFF increases the overall attack surface area of the system. These issues can be mitigated by starting with a single BFF, using shared libraries to avoid duplication, designing for backward compatibility, and centralizing security at the API gateway level.

It’s also crucial to recognize when a BFF is not the right solution. The pattern is overkill for applications with a single frontend, simple CRUD-heavy apps, or small teams where the overhead isn’t justified. If you already have a flexible backend API (e.g. with the ability to select and embed related data), the benefits of a BFF may be marginal. If your BFF starts accumulating business logic, it’s a sign you’re using an anti-pattern.

In such cases, alternatives like using an API Gateway with transformation capabilities, adopting GraphQL Federation, redesigning the backend API, or even performing aggregation on the client-side might be more appropriate.

Finally, as the root cause comes from an organizational disconnect, you can try to redistribute responsibilities so that frontend and backend engineers work together, and split teams by domain (e.g. product teams) rather than by technology (frontend vs backend).

Conclusion

The Backend-for-Frontend pattern is a powerful solution for specific architectural challenges, but it’s not a silver bullet.

Its success hinges on organizational buy-in, clear ownership by frontend teams, and an iterative approach. The best way to start is with a pilot project to measure its impact on performance and development velocity. If you need help getting started, feel free to reach out to us at Marmelab.

Ultimately, the best architecture is the one that empowers your teams to ship value to users quickly and efficiently. If a BFF helps you achieve that, it’s worth the investment.

Authors

Marmelab founder and CEO, passionate about web technologies, agile, sustainability, leadership, and open-source. Lead developer of react-admin, founder of GreenFrame.io, and regular speaker at tech conferences.