Learning Collaboration with Serious Games

Collaboration is often described as the cornerstone of effective teamwork, yet it remains one of the most difficult skills to put into practice. Serious Games offer a powerful way to address this challenge: by combining play with purpose, they create a safe environment where teams can test new approaches, reflect on their dynamics, and strengthen how they work together.

We had the opportunity to explore this in depth a few weeks ago at #play14, an international event dedicated entirely to Serious Games. Over several days, participants from diverse backgrounds came together to share methods, exchange experiences, and engage in workshops designed to foster collaboration and learning.

In a previous article, we introduced our top 10 icebreakers, activities aimed at building trust and establishing connections at the start of a session. But icebreakers are just the beginning. Once a group is engaged, the real focus shifts to developing deeper collaborative skills.

Out of all the workshops about collaboration we joined, five stood out above the rest, the ones that challenged our assumptions, sparked lively debates, and left us buzzing with ideas to take back to our own teams.

Collaborating Our Way Out of an Invisible Maze

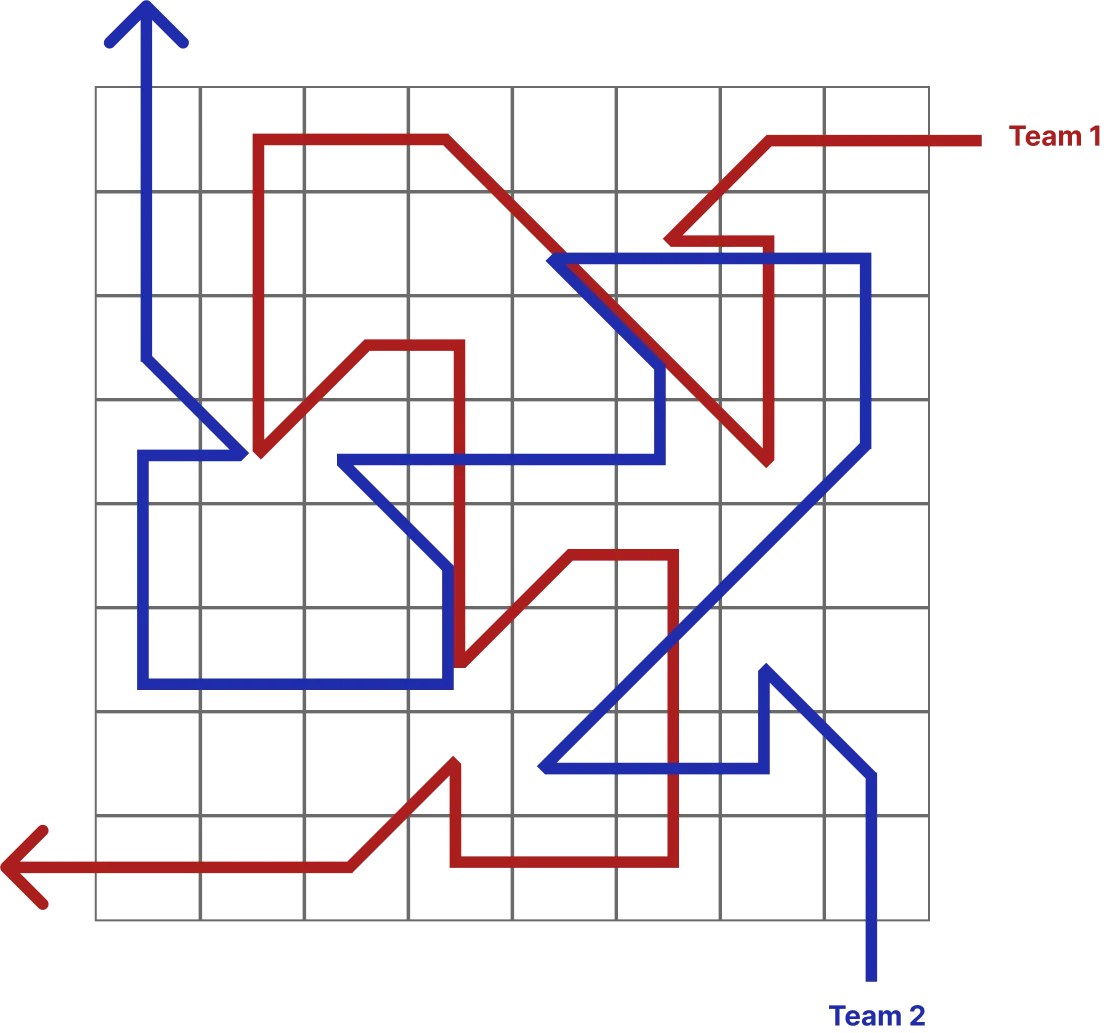

The Ultimate Maze is a challenging and engaging team activity where 3 to 4 players must navigate an invisible maze to find the correct, pre-defined path to the exit. The maze is laid out as a 7x7 grid, with each square measuring approximately one square meter.

Each team is guided by a facilitator who knows the correct path through the maze. Players move one cell at a time, horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Upon stepping into a cell, the facilitator immediately tells the player whether to continue or return. The catch? Players must rely solely on this feedback and their teammates’ silent signals to solve the puzzle.

Each team has to solve the same puzzle, but rotated at 90 degrees to avoid easily seeing the other team’s progress.

Game Rules

- Preparation Phase: Before entering the maze, teams are allowed time to develop a strategy.

- Silence During Play: Once a team begins navigating the maze, verbal communication is no longer allowed.

- No Tools: Teams must solve the maze without using any external aids or tools.

- One Player at a Time: Only one team member may be inside the maze at any given moment.

- Consequences of a Wrong Step: If a player steps on an incorrect cell, they must return to the start by retracing the correct path they have discovered so far.

- Team Rotation: After one player exits the maze, another teammate must enter and attempt the maze.

- Full Team Completion: Once a player successfully reaches the end, all remaining team members must complete the maze as well.

Insights and Strategy

This game stands out for its emphasis on non-verbal communication and collaborative memory. Throughout the challenge, teams often discover that some members have stronger spatial memory from direct experience, while others remember the path better by observing.

An effective strategy we uncovered involves intentional failure: players may deliberately step on an incorrect cell to quickly end their turn, allowing a teammate with a stronger memory to attempt the maze again sooner. Once a player reaches the end, they can assist the others using hand signals or other silent cues to guide them through.

Learn more about the Ultime Maze on the #play14 website

Multiplayer Chess to underline the importance of a common strategy

In this workshop led by Pascal Besson, we explored how to play chess as a team. Our group consisted of seven players with varying skill levels, from casual beginners to more experienced players familiar with strategic techniques.

We tested several multiplayer variants, but the one I found most interesting was the version where actions were delegated within the team.

- Split the group into two teams.

- For each turn, assign one “brain” player and one “hands” player per team.

- On their team’s turn, the brain player names a piece (e.g. “bishop”), and the hands player must move it, following standard chess rules. If multiple pieces of the same type exist (e.g. two bishops), the hands player chooses which one to move.

- After each turn, roles rotate: the hands player becomes the next brain, and a new teammate takes the hands role.

This version of the game can also be played cooperatively, with two players on the same team competing against the computer. To better understand how it works, here’s a sample game with Aronian and Maxime Vachier-Lagrave.

I really enjoyed this version because it highlights how it’s important to have aligned strategies before starting the project and pay attention to your team members so you can move forward together.

For example, if a “brain” is stronger than a “hands” player, it must try to imagine moves that the hand will be able to see, even if it means ignoring attractive moves, otherwise, the team will lose.

How to Improve a Process: a Workshop About 5S

This workshop, hosted by Francesco Di Martino, focused on improving processes through the application of the 5S methodology. It was divided into two parts: a brief theoretical introduction to the 5S principles, followed by a hands-on serious game that demonstrated their practical application.

The 5S Methodology

The 5S methodology is a workplace organization system designed to enhance efficiency, safety, and productivity. It consists of the following five steps:

- Seiri / Sort: Eliminate unnecessary items from the workspace.

- Seiton / Set in order: Arrange necessary items for easy access and use.

- Seisou / Shine: Clean and inspect the workspace regularly.

- Seiketsu / Standardize: Establish consistent practices and standards.

- Shitsuke / Sustain: Maintain and review standards continuously.

The Serious Game

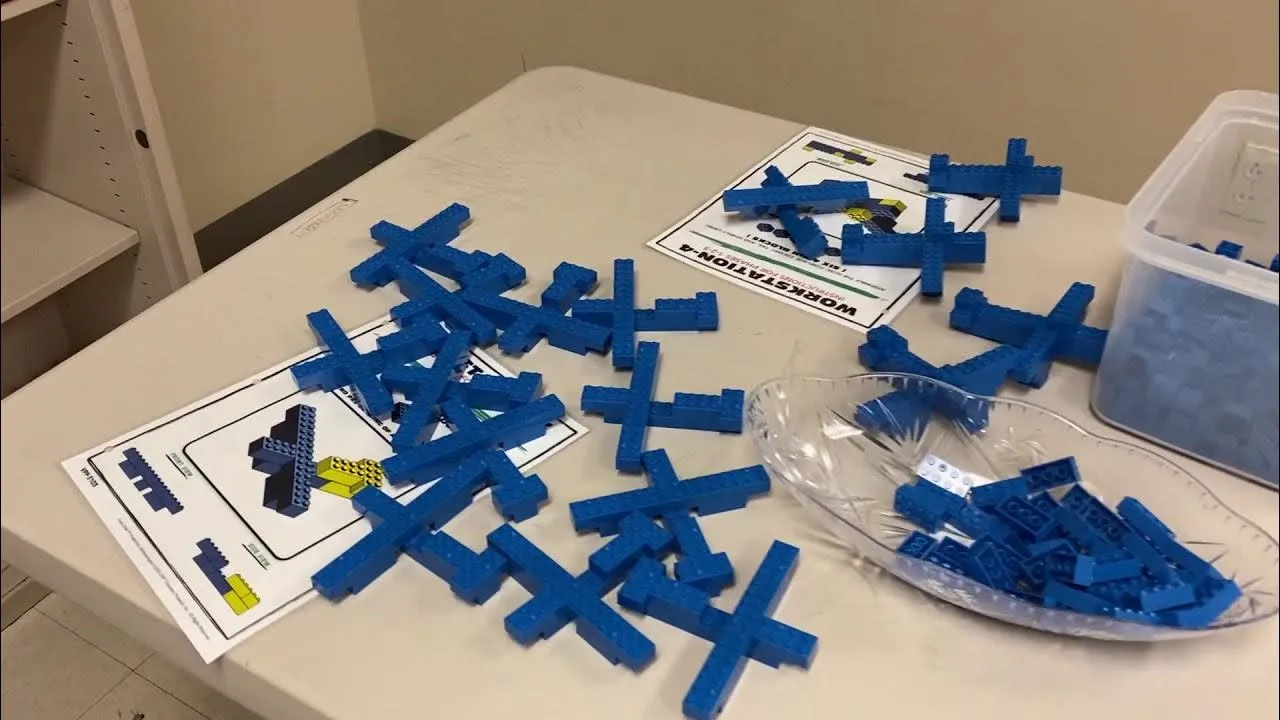

We applied the 5S methodology in a simulated environment involving an airplane manufacturing process. For the players, the objective was to build as many Lego airplanes as possible in a given time. Aside from the facilitators, the game unfolded over three timed rounds and involved five players:

- The Client – orders airplanes based on color

- The Process Manager – takes client orders and oversees production

- The Builder – constructs the planes

- The Warehouse – supplies components to the builder

- The Quality Controller – ensures finished products meet quality standards

Round 1 – Initial Process

At the beginning, each participant (except the process manager) was stationed in different corners of the room. Communication and workflow were fragmented. The team failed to produce a single Lego plane and completely overlooked the role of the quality controller. We took a moment to identify several issues and how solve it:

- Unclear process instructions: Text-based explanations were replaced with a visual workflow diagram (Standardize).

- Disorganized warehouse: The space was cluttered by components that were not useful to build planes. Furthermore, components were unsorted and mixed up with useless pieces. These were removed or sorted by shape and color (Sort).

- Poor layout: Players were too far apart, so we reorganized around a central table to encourage collaboration (Shine). This eased communication and reduced the time required to build a plane.

- Inefficient tool setup: A shadow board was introduced to organize the parts needed for assembly (Set in order). The shadow board ensured that the builders had all the necessary pieces to build the Lego planes and reduced round trips to ensure the quality.

Round 2 – Improved Workflow

With these changes, the second round began. The team managed to build a few planes, but a new issue emerged: the process manager and quality controller were no longer contributing effectively to the streamlined process as most of the work was done by the warehouse and the builder. This is due to the fact that the team communicated efficiently without any supervision, and that the quality was included in the build process.

Round 3 – Optimized Roles

To address this, we reassigned the process manager and quality controller to assist as a second builder and in the warehouse (Sustain). This optimization enabled the team to fulfill all client orders during the final phase.

Key Takeaways

We learned that integrating quality checks directly into the process improves both safety and product quality. The 5S methodology can significantly boost productivity by promoting better organization and clearer roles.

These principles are not limited to physical workspaces, they can also be applied to digital workflows to enhance efficiency, comfort, safety, and security.

I definitely recommend this serious game to improve collaboration in a team and applying the 5S methodology to improve the processes.

The Perception of Time

We are not referring to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, but to a more everyday phenomenon: the subjective perception of time.

Time itself is standardized and rigorously defined. International systems establish what constitutes an instant, a second, or a duration, and these units can be measured with extraordinary precision. Yet despite these standards, human perception of time is not absolute. Each individual experiences the passage of time differently, influenced by attention, memory, and psychological state.

A simple experiment illustrates this divergence:

- Any number of participants may join.

- A facilitator measures time with a clock.

- Participants close their eyes and attempt to reopen them after what they believe is one minute.

- The facilitator records the exact moment each participant opens their eyes.

- The exercise concludes once all participants have opened their eyes.

The results are often striking. In one instance, the first participant reopened their eyes after only 45 seconds, while another waited as long as 90 seconds. Only a few were close to the actual one-minute mark.

This demonstrates a key point: although time can be measured with scientific objectivity, its perception remains inherently subjective, shaped by cognitive and emotional factors unique to each individual.

Why Can’t We Trust Estimates?

At Marmelab, we use estimates to provide visibility and help assess which features can realistically fit into a sprint. We also know how difficult estimation is and we constantly remind clients and users that an estimate is not a commitment or a goal.

This serious game is a great way to highlight just how unreliable estimates can be. The game is easy to set up, quick to play, and inspired by the steps of a real agile project.

Like any agile process, the game unfolds in three stages, repeated across several iterations with a retrospective after each one:

- Explain what will be done

- Estimate the effort required

- Implement the task

These steps are repeated three times, with a short retrospective after each round to improve the next.

First Iteration: Blind Estimation

How it works:

- Without giving details, select a volunteer who will walk a short, simple distance (e.g., 20 meters).

- Ask each participant to estimate how long it will take the walker to go from point A to point B at a normal pace.

- Collect everyone’s estimates individually (they don’t need to agree).

- Record all estimates on a board.

- Have the walker complete the walk, and measure the actual time.

Retrospective:

In this first attempt, estimates vary widely because no one has a reference point for the walker’s speed. Each participant uses their own assumptions, such as imagining their own walking pace. As in a first sprint, estimates are disconnected from reality.

Second Iteration: Estimation with a Reference

How it works:

- Ask participants to estimate again the same task

- Ask and measure the walker to repeat the same route at the same pace.

Retrospective:

This time, estimates are more consistent and closer to the first duration. In fact, participants learned from the first iteration. However, the walker unconsciously walked faster during our workshop, finishing several seconds earlier. This highlights a key truth: the human factor makes estimates inherently unstable. The same task will not always take the same amount of time.

Now that the participants have two common experiences, the third estimation can begin.

Third Iteration: The Unexpected

How it works

- Collect a third round of estimates.

- The walker starts again at the same pace.

- This time, the facilitator introduces an unexpected interruption (e.g., stepping in, shaking the walker’s hand, and chatting briefly).

Retrospective:

Participants’ estimates, informed by the first two iterations, are more consistent than ever. Yet the actual outcome diverges significantly due to the interruption. This demonstrates that even the best-calibrated estimates cannot account for unforeseen events.

This serious game illustrates that:

- Estimates are based on past experiences, which means they improve over time but remain relative.

- Variability and human factors ensure that the same task won’t always take the same effort.

- Unexpected events can completely invalidate even the most careful predictions.

In short, estimates are useful for discussion and alignment, but they should never be mistaken for guarantees.

Conclusion

Collaboration is a key skill when it comes to work as a team. Serious games provide a practical and engaging way to strengthen your team members’ collaboration skills.

In this article, we’ve explored five games that provide practical ways for teams to improve their collaboration in any industry. Our next article will focus on communication and how serious games can be used to improve it in many situations such as giving better feedback, navigating verbal conflicts, and encouraging clear, impactful questioning.

Authors

Facilitator at Marmelab, she lives with two rabbits and loves playing boards games.

Full-stack web developer at marmelab, Jonathan likes to cook and do photography on his spare time.