Spec-Driven Development: The Waterfall Strikes Back

Spec-Driven Development (SDD) revives the old idea of heavy documentation before coding — an echo of the Waterfall era. While it promises structure for AI-driven programming, it risks burying agility under layers of Markdown. This post explores why a more iterative, natural-language approach may better fit modern development.

The Rise of Specification

Coding assistants are intimidating: instead of an IDE full of familiar menus and buttons, developers are left with a simple chat input. How can we ensure that the code is correct with so little guidance?

To help people write good software with coding assistants, the open-source community designed a clever way to guide a coding agent. Based on an initial prompt and a few instructions, an LLM generates product specifications, an implementation plan, and a detailed list of tasks. Each document depends on the previous one, and users can edit the documents to refine the spec.

Eventually, these documents are handed over to a coding agent (Claude Code, Cursor, Copilot, you name it). The agent, now properly guided, should write solid code that satisfies the business requirements.

This approach is called Spec-Driven Development (SDD), and several toolkits can get you started. To name a few:

- Spec-Kit by GitHub

- Kiro by AWS

- Tessl by Tessl

- BMad Method (BMM) by BMad Code

If you want a comparison of these tools, I recommend the excellent article Understanding Spec-Driven-Development: Kiro, spec-kit, and Tessl by Birgitta Böckeler.

The Markdown Awakens

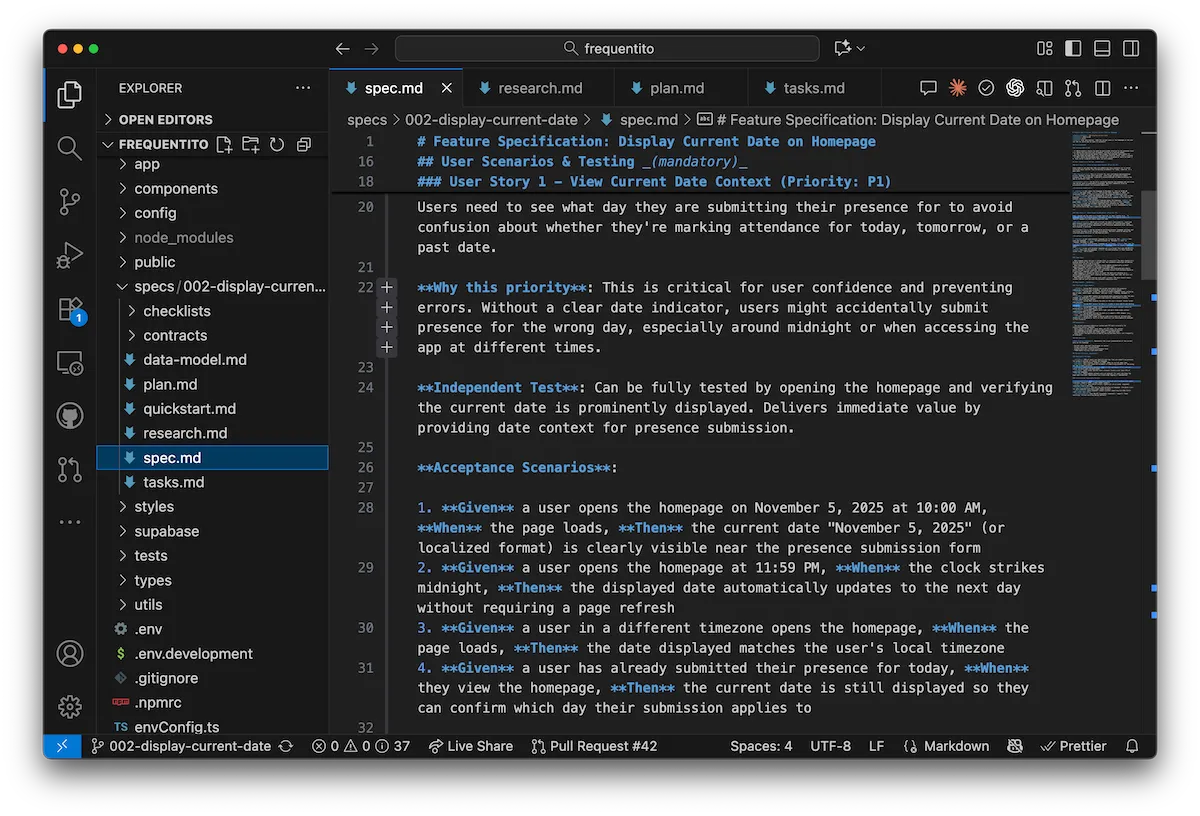

How does a spec look? It’s essentially a bunch of Markdown files. Here’s an example using GitHub’s spec-kit, where a developer wanted to display the current date on a time-tracking app, resulting in 8 files and 1,300 lines of text:

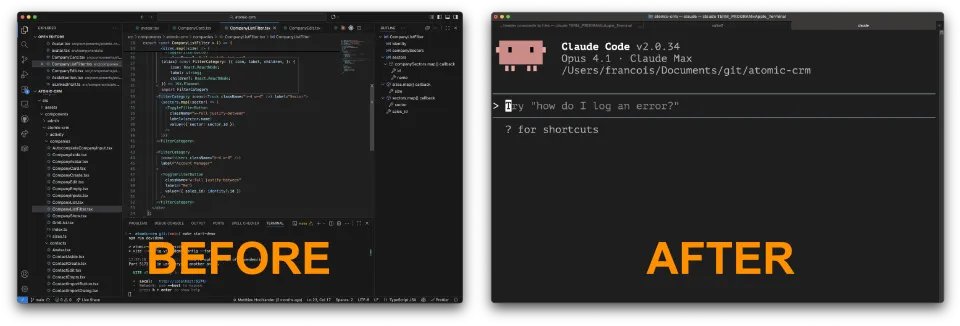

Here’s another example using Kiro for a small feature (adding a “referred by” field to contacts in Atomic CRM):

Requirements.md - Design.md - Tasks.md

At first glance, these documents look relevant. But the devil is in the details. Once you start using SDD, a few shortcomings become clear:

- Context Blindness: Like coding agents, SDD agents discover context via text search and file navigation. They often miss existing functions that need updates, so reviews by functional and technical experts are still required.

- Markdown Madness: SDD produces too much text, especially in the design phase. Developers spend most of their time reading long Markdown files, hunting for basic mistakes hidden in overly verbose, expert-sounding prose. It’s exhausting.

- Systematic Bureaucracy: The three-step design process is excessive for most cases. Specs contain many repetitions, imaginary corner cases, and overkill refinements. It feels like they were written by a picky clerk.

- Faux Agile: SDD toolkits generate what they call “User Stories,” but they often misuse the term (e.g. “As a system administrator, I want the referred by relationship to be stored in the database” is not a user story). It doesn’t cause bugs but it’s distracting.

- Double Code Review: The technical specification already contains code. Developers must review this code before running it, and since there will still be bugs, they’ll need to review the final implementation too. As a result, review time doubles.

- False Sense of Security: The SDD methodology is meant to keep the coding agent on track, but in practice, agents don’t always follow the spec. In the example above, the agent marked the “verify implementation” task as done without writing a single unit test—it wrote manual testing instructions instead.

- Diminishing Returns: SDD shines when starting a new project from scratch, but as the application grows, the specs miss the point more often and slow development. For large existing codebases, SDD is mostly unusable.

Most coding agents already have a plan mode and a task list. In most cases, SDD adds little benefit. Sometimes, it even increases the cost of feature development.

To be fair, SDD helps agents stay on task and occasionally spots corner cases developers might miss. But the trade-off (spending 80% of your time reading instead of thinking) is, in my opinion, not worth it.

Revenge of the Project Manager

Maybe SDD doesn’t help much today because the toolkits are still young and the document prompts need refinement. If that’s the case, we just need to wait a few months until they improve.

But my personal opinion is that SDD is a step in the wrong direction. It tries to solve a faulty challenge:

“How do we remove developers from software development?”

It does so by replacing developers with coding agents and guarding those agents with meticulous planning.

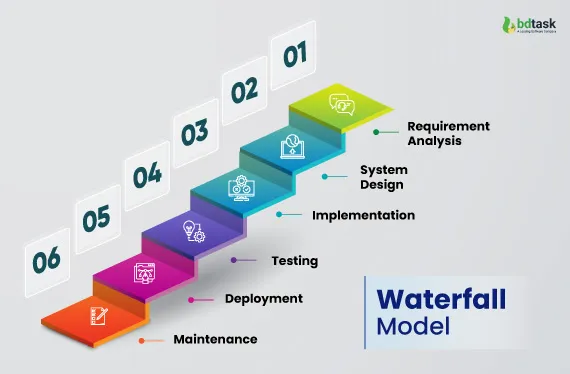

In that sense, SDD reminds me of the Waterfall model, which required massive documentation before coding so that developers could simply translate specifications into code.

But developers haven’t been mere executors for a long time, and Big Design Up Front has proven to fail most of the time because it piles up hypotheses. Software development is fundamentally a non-deterministic process, so planning doesn’t eliminate uncertainty (see the classic No Silver Bullet paper).

Also, who is SDD really for? You must be a business analyst to catch errors during the requirements phase, and a developer to catch errors during design. As such, it doesn’t solve the problem it claims to address (removing developers), and it can only be used by the rare individuals who master both trades. SDD repeats the same mistake as No Code tools, which promise a “no developer” experience but actually require developers to use them.

A New Hope

Agile methodologies solved the problem of non-deterministic development by trading predictability for adaptability. I believe they show us a path where coding agents can help us build reliable software, without drowning in Markdown.

Give a coding agent a simple enough problem, and it won’t go off the rails. Instead of translating complex requirements into complex design documents, we should split complex requirements into multiple simple ones.

I’ve successfully used coding agents to build fairly complex software without ever looking at the code, by following a simple approach inspired by the Lean Startup methodology:

- Identify the next most risky assumption in the product.

- Design the simplest experiment to test it.

- Develop that experiment. If it fails, go back to #2. Otherwise, repeat starting from #1.

Here’s an example: this 3D sculpting tool with adaptive mesh, which I built with Claude Code in about 10 hours:

I didn’t write any spec. I just added small features one by one, correcting the software when the agent misunderstood me or when my own idea didn’t work well. You can see my instructions in the coding session logs: they’re often short and vague, and sometimes lead to dead ends, but that’s fine. When implementing simple ideas is cheap, building in small increments is the fastest way to converge toward a good product.

Agile methodologies freed us from the bureaucracy of waterfall. They showed that close collaboration between product managers and developers eliminates the need for design documents. Coding agents supercharge Agile, because we can literally write the product backlog and see it being built in real time—no mockups needed!

This approach has one drawback compared to Spec-Driven Development: it doesn’t have a name. “Vibe coding” sounds dismissive, so let’s call it Natural Language Development.

I do have one frustration, though: coding agents use text, not visuals. Sometimes I want to point to a specific zone, but browser automation tools aren’t good enough (I’m looking at you, Playwright MCP Server). So if we need new tools to make coding agents more powerful, I think the focus should be on richer visual interactions.

Conclusion

Agile methodologies killed the specification document long ago. Do we really need to bring it back from the dead?

Spec-Driven Development seems born from the minds of CS graduates who know their project management textbooks by heart and dream of removing developers from the loop. I think it’s a missed opportunity to use coding agents to empower a new breed of developers, those who use natural language and build software iteratively.

Let me end with an analogy: coding agents are like the invention of the combustion engine. Spec-Driven Development keeps them confined to locomotives, when we should be building cars, planes, and everything in between. Oh, and just like combustion engines, we should use coding agents sparingly if we care about the environment.

Authors

Marmelab founder and CEO, passionate about web technologies, agile, sustainability, leadership, and open-source. Lead developer of react-admin, founder of GreenFrame.io, and regular speaker at tech conferences.